We talked to Heather Rose Jones about the eternal popularity of Regency novels, what magic can bring to a historical narrative and how class, gender and sexual identity intersect in women’s stories.

The Regency is a popular historical setting for writers. What drew you to this era?

Like a lot of authors, I fell in love with the setting through Regency romances–both the literature of the time, like the works of Jane Austen, and the extremely popular modern genre inspired by the works of Georgette Heyer. One of the inspirations for the Alpennia series was wanting to write Heyeresque romance where the women fell in love with each other.

Regency fiction is, in some ways, its own thing, distinct from historical fiction. It has a lot of the same appeal as writing fan fiction, where you have this alternative world with a shared set of rules and tropes and conventions that everyone can play in together without having to focus too strictly on historic plausibility. The Alpennia books aren’t technically Regency stories since they aren’t set in England, but that was very much the look-and-feel I was aiming for.

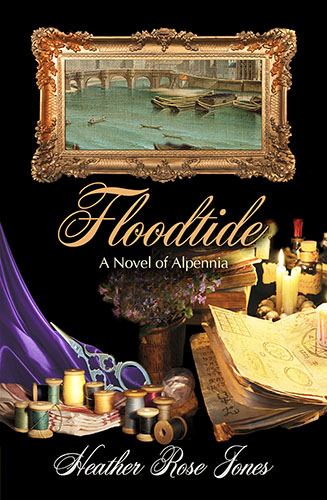

Floodtide deviates fairly strongly from the prototypical Regency in that it’s not a romance and the protagonist is working class with no expectations or aspirations to find herself plucked up into high society.

Apart from the popularity of the Regency romance genre, I think part of the appeal of the early 19th century Europe is that it’s a world on the cusp of massive changes. Political systems were in upheaval, warfare had changed, economies were in transition, colonialism was having far-reaching consequences, the Napoleonic wars had serious demographic impact. It was a time when you have people trying to live ordinary lives in extraordinary times. I think that transition between old and new is one of the reasons we see Regency magic as an identifiable sub-genre. The Enlightenment was challenging anti-rational worldviews, but the resulting world wasn’t quite “modern” yet.

It felt like a natural time to set stories about a culture steeped in mysticism and magic but grappling with seismic changes.

Historically, women have had fewer rights and were not able to choose their destinies with the same freedom as men. Did you choose a historical setting to explore and / or challenge this view?

I’d argue that we’re still in an era when women have fewer de facto rights and aren’t able to choose their destinies with the same freedom as men. It may be easier to draw the contrasts in past centuries because we aren’t swimming in them. But every setting, whether historic or modern, is a context for exploring gender power differentials and the ways in which women accepted or challenged them.

I didn’t specifically use history as a lens for gender inequity, though the distinctions are sharper because they’re more distanced from everyday forms of that inequity. It can be satisfying to have my characters directly confront barriers to education or to economic independence or to inheritance.

But conversely, an early 19th century setting gives me a context to show women supporting each other and finding ways to subvert the patriarchy that are as satisfying as the barriers are frustrating. Women of that time–especially unmarried women–moved through an overwhelmingly female world. I write stories that focus strongly on women’s networks and support systems, and those stories often make more sense in the past than the present.

For the protagonist of Floodtide, class distinctions are more immediate than gender distinctions, but she’s very aware of how gendered rules affect her employers, and the fine line between helping to work around them and enabling social disaster.

Why did you decide to include magic in Alpennia? What does adding a speculative element to historical fiction enable you to do differently?

There’s a practical answer and a structural answer. The practical one is that SFF is my “native tongue.” By structuring the Alpennia series as a fantasy, rather than a simple historical story, even a Ruritanian one, I could pitch it to the reading communities I feel most at home in. The f/f historical field is fairly small and disorganized. As historicals, the books would have sunk without a trace. As fantasy, they have a wider audience.

But the structural answer is that magic is a disruptive force, especially if it manifests randomly in the population. Magic creates opportunities for people to cross lines of class, gender, education, ethnicity. It can be an analogue for the rise of industrial wealth, or the theoretical class-blindness of Enlightenment salons, or the beginnings of celebrity culture.

Floodtide contrasts the more formal ceremonial magic featured in the previous books with the everyday practical magic–and magical frauds–that can be the last desperate hope of people seeking some control over their fates. For Margerit and Barbara in Daughter of Mystery, studying magic was an intellectual aspiration. But for Roz and Celeste in Floodtide, it’s a way of scrambling for scraps of advantage in surviving day to day and giving people hope who have little to hope for.

You manage the Lesbian Historic Motif Project. Do you feel lesbian voices have been missing from mainstream historical narratives?

Absolutely, with the caveat that I’m using a more fluid definition of “lesbian” than the modern sexuality category. At every level, historic forces have worked to dismiss, erase, and deny the existence of women’s love for each other and the ways in which bonds between women subvert our myths about the past. Writing historical fiction about women’s same-sex relationships isn’t wish-fulfillment and invention, it’s writing those women back into a past where they existed, in the same way that we need to write people of color back into the past, or trans people, or any of the other groups that we’re told didn’t exist there.

When I talk about a “past where they existed” I’m talking about things like the myth that the word “lesbian” in the sense of women who love women wasn’t in use until the 19th century. People will point to the Oxford English Dictionary as proof of this type of claim, not knowing that the OED deliberately excluded vocabulary and citations relating to women’s same-sex erotics.

But with that said, one of my goals with the Lesbian Historic Motif Project is to educate people–both authors and readers–about the ways in which lesbian-like lives in the past were different from our modern expectations. People had some very different understandings of the nature of gender, of the definition of sex, of what constituted deviant or admirable behavior. A lot of the fun of writing historical fiction is exploring those differences within our common humanity.

I explore a lot of different expressions of same-sex relationships in the Alpennia series. Margerit and Barbara are read by the world as “romantic friends” and thrive under society’s tacit agreement to ignore other possibilities. Jeanne de Cherdillac is a remnant of a more libertine tradition that allowed for outrageous behavior as long as you kept within certain lines. In Mother of Souls, Luzie enjoys the physical comforts of a same-sex relationship without thinking of it in the same category as her late marriage. In Floodtide, Roz has an entirely different and more precarious experience, not having class or wealth to protect her. All four experiences coexisted.

Pitch us Alpennia! What will tempt a reader into your world?

The short version is summed up on the badge ribbons I hand out at conventions: Swords! Women! Magic! There aren’t quite as many swords as I lead people to believe, but there are plenty of women and all types of magic. The best pitch is: if you’ve always wanted a swashbuckling romantic found-family adventure filled with talented and brainy women supporting and rescuing each other, then come to Alpennia! Floodtide makes a great introduction to the series, especially for those who like a diverse cast of younger protagonists.

Heather Rose Jones is the author of the Alpennia historic fantasy series: an alternate-Regency-era Ruritanian adventure revolving around women’s lives woven through with magic, alchemy, and intrigue. Her short fiction has appeared in The Chronicles of the Holy Grail, Sword and Sorceress, Lace and Blade, and at Podcastle.org. Heather blogs about research into lesbian-relevant motifs in history and literature at the Lesbian Historic Motif Project and has a podcast covering the field of lesbian historical fiction which has recently expanded into publishing audio fiction. She reviews books at The Lesbian Review as well as on her blog. She works as an industrial failure investigator in biotech pharmaceuticals.

You can find her on Twitter and Facebook. Floodtide is released 15th November 2019 from Bella Books.